Several revisionist artists have denied the atrocities perpetrated by Japanese in their Empire and during the Second World War. One of them is bestselling manga author Yoshinori Kobayashi.

by Takashi Fujitani

Media outlets throughout the world have often criticized Japan, in contrast to Germany, for its refusal to sincerely apologize for its war crimes. Examples of German contrition such as chancellor Willy Brandt’s silent “kniefall” in front of Warsaw’s Monument to the Ghetto Heroes in 1970, as well as President Richard von Weizsäcker’s elaborate admission of responsibility for countless atrocities and the Nazi tyranny in 1985 – such acts by Germany’s highest officials are often compared with Japanese leaders’ refusals to apologize or, at best, their ambiguous gestures of regret. To be sure, in the postwar years, especially with the partial ending of the Cold War in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Japanese officials have repeatedly issued apologies and other statements acknowledging guilt for various wartime and colonial atrocities. Most famously and consistently, in August 1993, Chief Cabinet Secretary Yōhei Kōno released what is now called the “Kōno Statement.” In that document he admitted that a governmental study had found that the Japanese military had been complicit in recruiting “comfort women” (a euphemism for sexual slaves) and that in many cases they had been taken against their will. He offered the Japanese government’s “sincere apologies and remorse to all those… who suffered immeasurable pain and incurable physical and psychological wounds as comfort women.” In the following years, state officials have on numerous occasions expressed their regrets and apologies, perhaps most resolutely by Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama, who on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the war’s end reiterated that Japanese “colonial rule and aggression” had “caused tremendous damage and suffering to the people of many countries.” For this he offered his “deep remorse” and “heartfelt apology.”

Nonetheless, many of Japan’s leaders have given the impression that their apologetic gestures are only formalistic and pragmatic. Thus, even though Prime Minister Shinzō Abe reaffirmed the “Kōno Statement” in 2014, in 2007 he had already refused to acknowledge that the “comfort women” had been recruited against their will. Furthermore, the repeated visits of Japan’s leaders (including Abe) to Yasukuni Shrine – the religious site honoring the war dead, including Class A war criminals – have symbolized Japan’s insufficient repentance. Similarly, while the latest agreement between South Korean and Japanese governments (announced in December 2015) promises more money to care for the former “comfort women”, the monetary compensation gives the impression of “hush up” money since Abe’s accompanying apology was not spontaneous but the result of negotiations with the South Korean government. And on the same day that the new agreement was made public, Abe’s wife paid her respects to the war dead at Yasukuni.

The role of popular culture

I begin with this juxtapositioning of the German and Japanese cases for two reasons: First, I want to suggest that while I realize that it is possible to make comparisons between German and Japanese contrition, I do not believe that such an exercise is useful because the situations which have led to their apparently different attempts to deal with their historical responsibilities are far too complex to compare in a simplistic way; and worse yet, such comparisons can serve as alibis for suspending self-criticism. For instance, a valorization of the German example may lead to the view that Germans and Europeans overall have atoned sufficiently for their past wrongs and need not do more. In my view, it is better to heed one of the main points of Weizsäcker’s famous speech, in which he insisted that rather than celebrate their achievements since the end of the war, the people of his nation should use the memory of the past as a “guideline” for the future. He urged his people to resist self-satisfaction and arrogance and to continue to reflect on such matters as the closing of borders to those in need, the persistence of discrimination of various kinds, and the ongoing burdens placed upon the people in the Middle East that have been the direct result of the earlier persecution of Jews in Europe.

Second, this stance on the ineffectiveness of gauging remorse comparatively is a starting point to consider the Japanese case, and in particular the role that popular culture has played in managing memories of WWII and Japanese colonialism. Popular culture constitutes a very powerful and effective cultural space for media that is helping to shape understandings of history and many other cultural, political, and social issues. While the writings of professional historians are certainly read, they cannot compete in sheer number and circulation with other media forms, beginning with manga, photographs, novels, movies, television, the internet, museums, and so on. Most students are likely to read history textbooks in order to do well on academic exams and then look elsewhere, including in manga, to develop their understanding and sentiments about history as a living past – in other words, a past which helps them to formulate their ways of living in the contemporary world.

Neo-nationalist writers, activists, and artists who have been adamant about denying Japanese wrongdoings have been particularly adept at utilizing popular cultural forms to circulate their historical views. Among them one of the most prolific and influential has been the manga artist Yoshinori Kobayashi, who has at least since the 1990s produced a seemingly endless stream of manga defending Japan’s modern wars and its Empire. His major works sell well into the hundreds of thousands and the three volumes of On War have reportedly sold more than a total of 1.6 million copies. In manga such as On War, On Taiwan, On Okinawa, New Thesis On Radhabinod Pal, On Yasukuni, On Greater East Asia, and so on, Kobayashi has given his national readership a self-congratulatory vision of Japan’s wars and Empire in the Asia-Pacific. These wars are portrayed as heroic efforts to liberate the peoples of the Asia-Pacific from the greed, racism and brutality of the white imperialist powers. Furthermore, Kobayashi’s manga show Japan as a benevolent Empire which developed the regions under its control economically and in other ways. This rendering of the Japanese Empire and the Second World War shares much with neo-nationalists involved in the textbook revision movement who have maintained that school children should be freed from what they call the “masochistic view of history.”

Grateful “comfort women”?

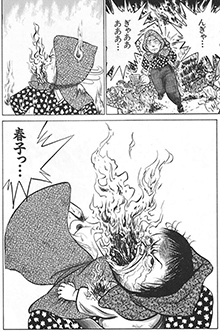

Kobayashi’s works are popular not only because they prey upon the weaknesses of many mainstream Japanese people for whom national self-adulation provides compensatory relief from the reality of social and economic problems. They also cleverly pick up fragments of historical truth behind which Kobayashi constructs a distorted view of Japan in world history. For instance, it is true that the Japanese launched many modernization projects such as building dams and irrigation systems, electrical plants, and railways throughout its Empire. But he fails to note that this development was intended to profit mainly the colonial rulers and the homeland – not the local people. Moreover, he minimizes Japanese atrocities such as the Nanjing Massacre and sexual slavery. Most outrageously, capitalizing on the fragment of truth that some “comfort women” may not have been directly forced into sexual slavery by the military, he drew pictures of happy “comfort women” in Taiwan who were supposedly grateful for the opportunity to move up in the world economically through their service as sex workers. Moreover, Kobayashi consistently employs a politics of comparative empires to make the point that in comparison to the European, and especially American nations and empires, Japan was far less exploitative and far more gracious and benevolent to those under its rule. His manga are filled with bits of truth about the history of Western expansion, conquest, seizures of land, colonial exploitation, racism, misogyny, religious intolerance, and violence against colonized peoples – in each case, lauding the Japanese Empire for its contrasting moral superiority. For instance, he denies Japanese racism against the colonized while at the same time drawing graphic scenes of white Americans’ brutality against African and Native Americans. He minimizes the scale of Japanese wartime violence and instead provides horrific depictions of Japanese civilians and even babies incinerated to death by American firebombings and the atomic bombs (see illustration above).

Kobayashi’s works are popular not only because they prey upon the weaknesses of many mainstream Japanese people for whom national self-adulation provides compensatory relief from the reality of social and economic problems. They also cleverly pick up fragments of historical truth behind which Kobayashi constructs a distorted view of Japan in world history. For instance, it is true that the Japanese launched many modernization projects such as building dams and irrigation systems, electrical plants, and railways throughout its Empire. But he fails to note that this development was intended to profit mainly the colonial rulers and the homeland – not the local people. Moreover, he minimizes Japanese atrocities such as the Nanjing Massacre and sexual slavery. Most outrageously, capitalizing on the fragment of truth that some “comfort women” may not have been directly forced into sexual slavery by the military, he drew pictures of happy “comfort women” in Taiwan who were supposedly grateful for the opportunity to move up in the world economically through their service as sex workers. Moreover, Kobayashi consistently employs a politics of comparative empires to make the point that in comparison to the European, and especially American nations and empires, Japan was far less exploitative and far more gracious and benevolent to those under its rule. His manga are filled with bits of truth about the history of Western expansion, conquest, seizures of land, colonial exploitation, racism, misogyny, religious intolerance, and violence against colonized peoples – in each case, lauding the Japanese Empire for its contrasting moral superiority. For instance, he denies Japanese racism against the colonized while at the same time drawing graphic scenes of white Americans’ brutality against African and Native Americans. He minimizes the scale of Japanese wartime violence and instead provides horrific depictions of Japanese civilians and even babies incinerated to death by American firebombings and the atomic bombs (see illustration above).

The deployment of these contrasting images of empires, in which Japan is always given moral superiority over the Western empires, has an effect similar to the politics of comparative remorse mentioned earlier – namely, it obstructs further ethical reflection on one’s own national past. One of Kobayashi’s and the wider circle of neo-nationalists’ favorite ways of using the politics of comparison to defend the Japanese Empire is to invoke the views of the Indian jurist Justice Radhabinod Pal. Justice Pal had offered a dissenting opinion at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal (the counterpart to the Nuremberg Trials) in which he sought consideration of the issues of Western colonialism and the atrocities of the Allied Powers. Many of Pal’s criticisms had considerable empirical, logical and moral force. For instance, he held that if a state’s leaders were to be charged with the type of war crimes being considered in Tokyo – by which he meant cases in which leaders explicitly ordered the execution of atrocities – there could be no more obvious instance than the dropping of the atomic bombs.

(No) absolution

Yet even here Kobayashi and his fellow neo-nationalists picked up decontextualized fragments of Pal’s reasoning while ignoring those pieces which do not conform to their defense of the Japanese Empire. For Pal did not intend to mobilize a politics of comparison to absolve the Japanese people and their leaders of their responsibilities for the horrors they had unleashed. He insisted that the “devilish and fiendish character of the alleged atrocities [committed by the Japanese] cannot be denied,” and further deplored the Japanese military conquest of Northeast China. In addition, he affirmed the punishments meted out to Japanese defendants in the thousands of war crimes trials that were taking place in roughly 50 locations throughout the Asia-Pacific region. But while Pal believed in the necessity of punishing those guilty of various crimes against humanity, he opined that there was no legal basis in international law for holding the limited number of the accused in the Tokyo Tribunal for conspiring to wage a war of aggression or for conspiring to commit atrocities. In other words, while he found the Tokyo Tribunal faulty on legal grounds, he condemned Japanese imperialism.

Perhaps the lesson to be learned from Japan’s neo-nationalist purveyors of popular culture as well as the often heard comparison of Japan’s lack of remorse compared to Germany’s, is that the politics of national and imperial comparison almost always seems to lead down the slippery slope of national alibis – alibis which too commonly have the effect of absolving all of us of our past sins.

Takashi Fujitani is the Dr. David Chu Chair Professor, Professor of History, and Director in Asia Pacific Studies at the University of Toronto. Most of his research has centered on the intersections of nationalism, colonialism, war, memory, racism, ethnicity, and gender. His major works include: Race for Empire: Koreans as Japanese and Japanese as Americans in WWII (UC Press, 2011). He is also editor of the series Asia Pacific Modern (UC Press).

e-mail: t.fujitani[at]utoronto.ca

Schreibe einen Kommentar